Extinct Irish Elk Turning Heads

Motorists driving by make ridiculously dangerous U-turns to come back and stare at this magnificent beast. Bicyclists risk near collisions as they stop dead in their tracks to take a closer look.

Thought to be long extinct, the giant creature stood a towering ten feet high with his antlers spanning eight feet.

How did this monstrous deer pull itself out of a peat bog and find its way to the little fishing village of Liscannor in County Clare? Just ask Andrew Carragher, the sculptor who created him.

Andrew cruised into Clare with the sensational sculpture, riding high on a flatbed trailer behind his large navy blue van.

The elk was constructed from hundreds of branches of twisted, turned and woven wood to form his muscular body and the enormous rack of antlers. The animal pulsed with energy. As if on high alert, the elk’s colossal head was turned around to look behind him, sensing a possible predator, or maybe a chance to mate.

He was on view in front of Ann Daly’s Atlantic Way Gallery, a terrific new addition to “The Strip” of little Liscannor.

The Artist

I spotted a blue-jean clad fellow with the aura of a woodsman, sitting on a low stone wall chatting with a young lad. I butted into their conversation and asked, “Are you the artist?”

“Yes, I am,” said the soft-spoken woodsman, who looked to be whittling at a moss-covered four foot branch.

“Sorry to interrupt,” I said apologetically. “That’s an amazing work of art you have created.”

Andrew Carragher, Irish sculptor

With his long, thick brown hair whipping in the breeze, he answered shyly, “Thank you very much.”

Small in frame, with a bushy brown beard, I searched for his eyes, covered by his long bangs, before engaging him further. I sensed an old soul behind them.

“Can you tell me more about it? What kind of wood did you use?”

With that, the artist excused himself from the boy, and got up from the stone wall to enlighten me. His hot pink smartphone was poking out of the pocket of his plaid flannel shirt. This modern piece of technology seemed to completely contrast to this otherwise connected-to-the-earth person.

Now standing, he was not much taller than me at 5’ 1”, and I noticed a bit of grey had crept into his beard.

“Some ash, alder and some sycamore,” he said as we both moved closer to the massive animal. Next to one of the big hoofs was a display of postcards featuring the sculpture in the clearing of a forest of tall evergreen trees. Price € 2.50.

I just happened to have that amount and handed it to the artist.

“You’re all right,” he said, not wanting to accept it.

I gave it to him anyway and picked up a card. On the back was his name and his website. Later, a visit to his site revealed that Andrew earned an Honors Degree in Fine Art Sculpture as a graduate of the West Wales School of Art, Glammorgan University.

The Great Irish Elk sculpture by Andrew Carragher, Ireland / Photo by Conor McEneaney

“Where was this picture taken?” I was curious about where he’d staged the arresting photograph on the front of the card.

“Slieve Gullion,” he replied, with a Sean Connery-esque kind of “shh-ing” lisp.

I couldn’t quite understand the word after Slieve, so he asked, “Can I write on the back of the card?”

I quickly fished out a pen from my black Prada messenger bag. Not only did he write “Slieve Gullion, Co. Louth/Armagh,” he began to draw a picture and explained, “This area is known as the mythical land of Ireland.”

The Mythical Land of Ireland

First, Andrew made a drawing that resembled a reclining pregnant woman. Up at the top of her belly, he drew a small rectangle and said, “There is a cairn here. On the twenty-first of December, the winter solstice, the light passes through an opening, and illuminates the cairn.”

“Is it like Newgrange?” I asked. Having been to Newgrange, I knew it was a prehistoric monument with a grand passage tomb built around 3200 BC. The passage leads into a chamber with three alcoves and they, too, are aligned with the rising sun at the winter solstice.

“Yes, like that,” he nodded.

Additional research later on informed that the summit of Slieve Gullion is the highest surviving passage tomb in Ireland. The monument dates back to between 4000 B.C. and 2500 B.C., making it up to 6000 years old. That means it could be 3000 years older than the Pyramids of Giza, and nearly 4000 years older than Stonehenge. Like Newgrange, the tomb is aligned to the setting sun at the winter solstice.

Andrew drew the mountain with the cairn. He also expertly rendered, no bigger than one inch high, a perfect map of Ireland, and put a dot where Slieve Gullion is located.

Again, when he was explaining that this whole area plays a prominent role in the mythology of Ireland, I couldn’t quite catch the word he was saying when describing a particular character. These Irish words sounded so foreign to my ears. He wrote: “Cuchullian.”

Cú Chulainn, the mythical Irish hero

Of course, that required more research. It turned out that the name can be spelled “CúChulainn,”or “Cú Chulaind,” or “Cúchulainn.” No wonder I was stumped! Regardless of the spelling, this mythological Irish hero was said to be an incarnation of the God Lugh (pronounced “Loo”), and he took the form of a fierce guard dog that he killed in self-defense. Then, as the story goes, he offered to take its place until a replacement could be reared. In more modern times, Cu Chulainn is often referred to as the “Hound of Ulster.”

What I found especially fascinating is that the legend of Cú Chulainn is very similar to the story of the Persian hero Rostam, the Germanic Lay of Hildebrand. It also calls to mind the Greek epic hero Heracles, suggesting that just like the Great Irish Elk that roamed vast distances by crossing the land bridges after the thick glacial ice had melted, other cultures in far flung places created similar myths in mind bridges of their collective consciousness.

To be the most famous son of Lugh was no small thing, considering Lugh was said to be a Celtic god of storms, especially thunderstorms, and possessed several magical weapons. One in particular, an invincible spear, is said to have never missed its target. And this spear was so bloodthirsty it would often endeavor to fight without anyone wielding it. Presumably, Cú Chulainn inherited the mantle of all this lore for future generations of warriors who would avenge the many murders of his mythical ancestors.

Scores of books have been written over the centuries about the wives, wars, and powerful magic attributed to these legendary figures. Suffice to say, our Great Irish Elk emerged from Andrew’s fertile imagination, carried in the well-read head of this County Louth native. County Louth, steeped in myth, legend and history, is named after the village Louth, which is in turn, named after Lugh.

“So this animal of yours is really monumental. How big did they really get?” I asked Andrew.

“It got to be seven feet at the shoulder and the antlers could span twelve feet. I would like to go bigger, but I couldn’t because then I couldn’t get it out of the shed I was working in.”

I was mesmerized by the giant creature, that looked as if it could bolt away at any moment. All I could manage was, “This is magnificent.”

Andrew, drawing a crowd now, was on a roll. “It was called the Great Irish Elk because this is where they found so many examples of the antlers. They roamed from here to Siberia and Canada. It ran across the whole northern hemisphere—of the whole planet. I think it got as far as China.”

The great Irish elk (reconstruction, museum exhibit)

We were all entranced. It really hit home then; I’d read that long ago Ireland was entirely land-locked before it became an island.

The artist expounded, “They were found in the bogs and the lakes. Even in Dublin.”

“There are bogs in Dublin?” I blurted out in astonishment.

“There are bogs everywhere. Even in Dublin,” he explained. “They did some excavating. Found the bones of a Great Irish Elk that was 20,000 years old.”

I loved listening to Andrew. The word “years” sounded like “yearsh.” “Horse” was “horsh.” “Person” was “pairshon.”

I gazed at the perfectly formed hoof of the giant animal. “How long did it take you to make him?”

“About seventeen months, on and off,” Andrew replied. “Probably four months, if I had worked on it straight through.”

At this point, Andrew realized he hadn’t asked, and said, “What is your name?”

I shook his tender hand and said, “Taba Dale.”

“Nice to meet you, Taba,” Andrew said warmly.

“What would a piece like this sell for?” I queried.

After a short hesitation, Andrew replied, “About 15,000 euro.”

That would be close to $17,000 (U.S. dollars). Good, I thought. I was glad he did not undervalue his work.

Taken by the Andrew’s Elk

Just then, a man on bicycle dismounted. With helmet in hand, he came over to admire the impressive elk sculpture.

In awe, he remarked to Andrew, “This is EX-traordinary!” Hardly able to contain himself, he continued, “I’m out in the country and I have a place. Something like… something like that would be… that’s just unbeeeeelievable. Do you have a website?”

Andrew gave him a card and said good-naturedly, “I would love to work with somebody to create something —to create something to their liking. Whatever it is. This is to my liking.”

The swank cyclist, sporting a neon yellow shirt and wrap-around sunglasses, said, “We’re staying with friends—they have an enormous place in Donegal.” He stared up at the elk’s gigantic rack of antlers, and gushed, “Something like that would be just fantastic. I must let them know about it.”

“I’m sure it would be a perfect setting for this animal,” Andrew replied.

“So how much is that?” The cyclist asked, as if price was no object.

Since I’d just asked the question myself, Andrew turned to me. “What did I say, Taba?”

Not missing a beat, I replied, “Upwards of 15,000 euro.”

“Jaysus!” the man said with a hearty laugh. “I can see it. I can see it. Maybe not for me, but it is absoluuuuuuuutely extraordinary!”

To keep the cyclist enthused, I asked Andrew, “Have you done a smaller version? Or could you do one?”

Andrew chimed right in, “I would love to do a commission. I would love to do a smaller version.”

The cyclist inquired, “What’s your background? Do you just work in wood?”

“I work in all materials. I work in glass as well.”

The exuberant cyclist reiterated, “This is absolutely EX-traooooordinary! Where are you based?”

“County Louth.” (Sounds like “Loud.”)

“In Louth!” The cyclist did a quick calculation and realized that is about 300 miles away.

“How come you’re down here?”

“Just spinning about,” Andrew said with a smile.

I asked the cyclist in jest, “How come you’re down here?”

“We’re over at the Doolin Folk Festival.”

The cyclist tuned into my accent and asked, “And where are you from?”

“Originally, Washington, D.C., but don’t hold it against me.”

I didn’t want to draw attention away from Andrew and his creation. I was glad when I heard the cyclist shout to his partner, “Rita, isn’t it amazing?”

“Yes, yes it is fabulous.” Rita agreed as she walked her bicycle over to us.

Rita’s mate reiterated, “Absolutely extra—oooooor—dinary! This is the sculptor here—the creator!”

The Great Irish Elk sculpture by Andrew Carragher, Ireland / Photo by Conor McEneaney

Andrew continued to answer more questions posed by the cyclist and Rita. “This piece here is ash, this is alder and a few random pieces like sycamore…the antlers—I picked them up very early—just had the frame right, had the stance right…not sure what kind of wood that is…like to find out for meself…”

I excused myself and said goodbye to Andrew. I hoped that the discussion with the cyclists would eventually lead to a sale or commission for him.

I wandered home in wistful contemplation, remembering the work of Deborah Butterfield that I saw at the Phoenix Art Museum when I first moved to Arizona. She is best known for her depictions of horses made from found objects and natural materials, such as wood.

I imagined Andrew’s Elk at the PAM, giving Butterfield’s sculpture, titled “Ponder (Reflexionar)” a run for its money; and making the statement: “There’s a new alpha male in town.”

Not the End of the Story

While I was immersed in writing The Great Irish Elk story and shared Andrew’s insight about how the area of Slieve Gullion played such a prominent role in the mythology of Ireland, I realized that he is truly an original thinker and is very connected to the world that surrounds him. For me, Andrew had expanded the intersection of art and other disciplines such as anthropology.

Then I wrote to Andrew and asked him to tell me more about his process creating his art. The intellectual power and warmth of what he came back with genuinely moved me. With Andrew’s permission I am happy to share his profound narrative about his art:

Hello Taba,

The Elk is a result of my investigation into my surroundings. I have always felt undernourished in terms of the explanation that is presented of Irish mythology and what the ancient stories really encapsulated.

I found an approach of study into my local landscape that is eternal, practical, logical and most importantly spiritual. This approach has brought me to a loving relationship with nature.

How so may you ask ! It begins with inspiration from years of study by Anthony Murphy and Richard Moore which is encapsulated in a book named Island of the Setting Sun.

The great Irish Elk is physically and more importantly spiritually valid in our collective history and ancestral memory. And for me it is fulfilling, attempting to reveal its essence. I hope this does not confuse things but the language that chose me was sculpture with nature’s raw material, showing the life of the trees in this instance reincarnated into what I hope does them justice.

Further study from this starting point has brought me to decode ancient mythology all around the world with its common practical and very spiritual journey through time. And its personification as time shifted in unison or regulation from the heavenly elements and relieved its god-like beauty in Earth’s nature which we can touch, see, and it nourishes our body and soul.

That eventually brought me to express what I have learned through my language of sculpture. This was a perfect medium to have a knowing relationship with nature or in my case trees.

Disengaging in preconceived thought or planning of construction was the only option for full expression, I was confronted with the option of approaching the material (fallen tree branches) devoid of logical selection. But lovingly trusting the branches would direct me to were it would express more than my human eye could see.

I am honored that you showed interest and enjoyed contemplating The Great Irish Elk. I believe the work you are carrying out in your writing books with your observations is highly commendable and of great importance.

Kindest regards,

Andrew

Bonnie Bovine – Part 1

By Taba Dale

Kevin and I are back in Liscannor, after completing two Golf & Music Tours to St Andrews and the Highlands. Our golfers played many of the iconic, Top 100 courses during the day, while our musicians, Paul Carroll & the Begley Brothers, entertained every night in local pubs. The Auld Grey Toon (St Andrews) will never be the same, that’s for sure.

We were in Scotland for nearly an entire month, taking an extra week with our friends Jane and Roger Franklin, to visit the Isle of Skye, Lewis and Harris in the Outer Hebrides, and South Uist.

Taba inside circle of Callanish Stones on Lewis

On the Trotternish Penninsula of Skye, we climbed the steep path to the large pinnacle of rock known as the Old Man of Storr. We explored the ethereal Callanish Stones on Lewis, which predate Stonehenge by 500 years.

Askernish: 11th hole, par-3, walking from Kevin’s tee (197 yds) to my tee (142 yds)

Back in County Clare…

Back in County Clare where Elsie & Lucy and the small herd of cows spend their days eating the juicy grass of Liscannor…

“Lucy, what do you think we should call the new girl?” Elsie asked.

“Oh, I don’t know. She’s so huge,” Lucy noted, spotting her large, white body grazing in the field.

The big new white cow grazing in the pasture

“Well, Batty the Battleship was what I call huge. She was so big and grey. I really miss her.”

“Me too Elsie,” Lucy agreed, “she was a dear sweet soul. She was an enormous help when we went to visit our cousins in France.”

“Oh please, don’t bring that up now,” Elsie mooed and hung her head.

“OK, so the giant white one — she is really a bonnie bovine,” Lucy said with a swish of her tail.

“Where did you come up with that? Have you been listening to our next-door neighbors?

“I did hear the brown-eyed American gal talk about Bonnie Prince Charlie,” Lucy confessed, “but apparently she doesn’t think he is so bonnie.” Brown Eyes said, ‘Maybe he was pretty, but he was an eejit and only escaped from Scotland after he botched the Battle of Culloden, by dressing up as an Irish spinning woman!’”

Elsie was aghast. “You know, Lucy, I’m really not political. Don’t get me started on that subject.”

“Sorry, sorry,” Lucy apologized. “But what about the monstrously big new white girl?

Elsie was pensive and then said, “She’s like a massive recumbent slab, isn’t she?”

“A what?” Lucy couldn’t believe her ears. “What in the world is that?”

Now it was Elsie’s turn to admit she was eavesdropping. “Must have been our human neighbors again — talking about seeing standing stones in the Outer Hebrides, and a stone circle in Daviot when they were in Aberdeen.”

Recumbent slab of stone circle, Longhead at Daviot, (Aberdeenshire) Scotland

Lucy shivered a little and asked, “Do you think they are into spiritual stuff?”

“Probably the gal is. The guy worships golf, so no, it would not be his thing.”

“Maybe our new white cow is spiritual too. What if we call her Daviot?”

Elsie concurred. “Good one Lucy. She deserves a very special name.”

Life Across the Pond

Tony Kirby

A better introduction and guide to the west of Ireland, you will never find anywhere. Photo by Taba Dale.

You will never know the beauty or the deeper heritage of the west of County Clare like you will if you go on a Burren Walk with Tony Kirby. Tony is originally from Limerick and after working in Dublin and Italy, he settled in County Clare. He is now a full-time walking guide and heritage consultant, based in the Burren.

One thing you would probably never expect, is to hear a W.B.Yeats (1865-1939) poem while on your walk. However, when we reached a magical rainforest (yes, in the Burren!), Tony stopped to explain the importance of what he defined as a “magisterial woodland.” When a lady in our group said, “You should quote ‘I walked into a hazel wood’,” Tony replied, “I’ll do a William Butler Yeats poem for you, Ann, but this one is very short. It’s called ‘Politics’ and to give you the context, when he wrote it, there is a war looming in the world and also, he is an aging gentleman.”

And then he recited:

How can I, that girl standing there,

My attention fix

On Roman or on Russian

Or on Spanish politics,

Yet here’s a travelled man that knows

What he talks about,

And there’s a politician

That has both read and thought,

And maybe what they say is true

Of war and war’s alarms,

But O that I were young again

And held her in my arms.

– W. B. Yeats, “Politics” from Last Poems (1938-1939)

Then of course later on, after the guided walk, I had to look up the one Ann asked Tony to recite. It is quite a bit longer and sublime. It is called ‘The Song of Wandering Aengus’ and here it is:

I went out to the hazel wood,

Because a fire was in my head,

And cut and peeled a hazel wand,

And hooked a berry to a thread;

And when white moths were on the wing,

And moth-like stars were flickering out,

I dropped the berry in a stream

And caught a little silver trout.

When I had laid it on the floor

I went to blow the fire a-flame,

But something rustled on the floor,

And someone called me by my name:

It had become a glimmering girl

With apple blossom in her hair

Who called me by my name and ran

And faded through the brightening air.

Though I am old with wandering

Through hollow lands and hilly lands,

I will find out where she has gone,

And kiss her lips and take her hands;

And walk among long dappled grass,

And pluck till time and times are done,

The silver apples of the moon,

The golden apples of the sun.

But then, it seems just as important to include the Nobel laureate, Seamus Heaney (1939-2013) in this story. Here is ‘Postscript’ from his book The Spirit Level: Poems:

And some time make the time to drive out west

Into County Clare, along the Flaggy Shore,

In September or October, when the wind

And the light are working off each other

So that the ocean on one side is wild

With foam and glitter, and inland among stones

The surface of a slate-grey lake is lit

By the earthed lightening of flock of swans,

Their feathers roughed and ruffling, white on white,

Their fully-grown headstrong-looking heads

Tucked or cresting or busy underwater.

Useless to think you’ll park or capture it

More thoroughly. You are neither here nor there,

A hurry through which known and strange things pass

As big soft buffetings come at the car sideways

And catch the heart off guard and blow it open.

When you read these words and picture Clare, or the Burren, or better yet, come over here yourself, you will begin to absorb the essence of Ireland. And in ten more lifetimes, you can find the wisdom in the soul of Ireland. But if you spend just one afternoon with Tony Kirby, you will shorten the number of lifetimes by a good few.

William Butler Yeats was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1923. He renovated an old tower house near the town of Gort in County Galway and named it Thoor Ballylee, Thoor being the Irish word for tower. From 1921 to 1929, Yeats and his family lived there so Yeats could be close to the beauty of the countryside and also be near his close friend, the writer, folklorist and playwright, Lady Augusta Gregory. With Lady Gregory and another neighbor, Edward Martyn who lived at Tullira Castle, they formed the Irish Literary Theatre in 1899. Then, in 1904, they became the co-founders of the Abbey Theatre.

From the top of the tower house, one can see views of the south of Galway, stretching all the way to the Burren. And should you be inclined to get a copy of Tony’s book, The Burren & The Aran Islands, A Walking Guide, he includes a walk at Coole Park and begins Route 12 with this excerpt from the W.B. Yeats poem ‘The Wild Swans at Coole’ (1919):

“The bell-beat of their wings above my head

Trod with a lighter tread…”

In Your Wheelhouse

There is still a controversy about where J.P. Holland, inventor of the submarine, was born…but that comes later.

I finally found a moment to go down to Egan’s pub in Liscannor and show Patrick Egan the proof of my about-to-be published book, A Summer in Ireland. After all, one entire story is about him and another is about the music I heard there one night.

When I showed Patrick a photo that I had taken surreptitiously on that night he said, “Oh that was early,” meaning around 11:30 PM or midnight!

“That’s Mirabelle Gilis,” he said pointing to the dark-haired violinist. “She’s a classically-trained famous French fiddle player. Used to be a friend of a barmaid we had here back then.”

In the photo, Mirabelle was sitting at the small square wooden table in front of me where appreciative traditional Irish music lovers sent over three frothy pints of Guinness for her and another vagabond guitarist, whose agile fingering added extra sparkle to the whole magical music session.

I pointed to the three staggered pints of the black stuff, perfectly poured with their nice creamy heads in their trademark flared glasses and told Patrick, “I really like these three pints of Guinness—they look just like notes on a scale,” as I recalled how every molecule of my body had been infused with the music in the air.

Patrick nodded and smiled. “You left before the guy in the corner started singing. It was standing room only by then. It’s on YouTube! Have you seen it?”

Not only had I not seen it, I was a bit dumbfounded, as I was trying to be so discreet just snapping a quick photo or two, not wanting to annoy the musicians or be perceived as an ‘ugly American!’ Don’t get me wrong, I’m well aware that the Irish are known to be quite convivial and pubs are the place where they all go for the ‘craic’, but the atmosphere at that moment was almost other-worldly—it was like I was witnessing some kind of spiritual convergence and I just didn’t want to do anything to disturb the vibration.

In fact at one point, a hush fell over the room when an older gentleman came through the door and Kevin whispered to me, “I think that is the McPeake patriarch from Belfast.”

I told Patrick what Kevin had said and asked, “Was that him?”

“Yeah,” he beamed proudly, “the head of the McPeake family was indeed here. His name is Francis.”

To understand the significance of his presence, you need to be aware that it was at the McPeake School of Music in Belfast where John Lennon learned to play the Uilllean Pipes (the bagpipes of Ireland, pronounced ill’-in), under the tutelage of this very revered teacher, Francis McPeake III, of the four generations of “folk-royalty,” when it comes to Irish Traditional Music.

When he read the bit about another musician that Sean Scanlan described as, “Our own Johnny Cash,” Patrick laughed and agreed, “Yeah, we call him ‘Johnny-No-Cash’. He winked, then added, “Or we say he is one of the Elderly Brothers.”

It was a special night. No doubt about it.

As soon as we sat down together, Patrick had graciously ordered a glass of wine for me. It was truly a treat, as Patrick is also known to be an extraordinary wine connoisseur. I was enjoying this rare tete-a-tete with the congenial proprietor and marveled at the extensive selection of liquid choices, but not wanting to end up too tipsy I asked, “Do you serve any food here?”

“Yes, we have sandwiches now,” explained Patrick, “Charo (his wife) bakes the bread every day. We brought in a palette of the dough from Barcelona.”

Ah, that’s good to know—I might hang out here a little bit more now.

We switched back to the topic of books with him suggesting a heavier, coated paper for my book cover. He got up and disappeared into another room for a few minutes, then returned with a book called County Clare, An Introduction of the Architecture, so I could see and touch exactly what he was talking about.

I knew that Patrick was a serious collector of books but he appeared to be so knowledgeable on publishing, my curiosity compelled me to ask, “How do you know so much about all this?”

“Years ago when books were books,” (meaning before the digital craze got started) “I did some publishing and I also used to make DVDs.”

“DVDs? Of what?” I said, astonished.

He shrugged. “I used to be in television when I was in London. From 1983 to 1987 I was a consultant to Channel 4 and I made documentaries about Art and Architecture.”

Amazing. This man is truly amazing.

The conversation then switched to the story I wrote called “Population: 67” which is how many people Patrick told me lived in Liscannor that summer of 2010. In particular I brought up the topic of where J.P. Holland was born, since some of my research (and at least one Liscannor native) claims he was born in the town. Holland would undoubtedly be the most famous person from this tiny corner of County Clare, so the town fathers would fiercely protect what was believed to be his birthplace.

“He was born in Killaloe,” Patrick stated emphatically. “He would have been born in his mother’s family home. His father married a Scanlon. (I made sure to ask if it was spelled ‘on’ or ‘an’.) He was married twice actually, both times to a Scanlon.”

When I commented at the oddity of that he put a finer point on it and added, “And there is no birth ‘cert’ in Liscannor.”

Well that fact speaks volumes, doesn’t it?

He was a little bit amused that my story mentioned him giving me an up close look John Speed’s 17th century hand colored map showing the old name “Liskeny” in the part of Clare that is now Lahinch. I was pleased as punch when he complimented me for my good memory. I wish I knew why certain words or names stick in my brain. Maybe it comes from being a cartographer in another life?

While on the topic of names, was when Patrick said, “I used to fish for years out in the bay, and you know that rock that stands up from the water near the Cliffs of Moher?”

“I’ve only seen it in photographs,” I said as I drew a little picture of the sea stack. To which he enthused, “That’s it! Well, it has four different names. Some people call it An Bhreannan Mor. The fisherman call it Inis Mhicil. And if you’re from the Aran Islands, they call it Inis Mhic Domhnall. And then it is sometimes called Stokeen Rocks.”

This prompted a sad shake of Patrick’s head. “I fished for years with Brown on that boat that sank last week off Spanish Point. It used to be Brown’s boat.”

Of course I had heard that sorrowful news that Kevin brought home one night after meeting Sean for a couple of pints at Egan’s last week. There were two men who drowned. It was a bone-chilling fact that they were found close together in the wheelhouse of the trawler, the Lady Eileen.

The story was so shocking because they were known to be experienced fishermen and the sinking happened so suddenly. I said consolingly, “Do they know yet what caused it?”

“It was overloaded,” he sighed. “They had a steel frame wire enclosure to hold the nets on the back of the boat and it was too heavy.”

He gestured with his hand to show me how the stern of the boat would have sunk first with the two fisherman in the wheelhouse. “They were both in the wheelhouse because they were on their way home. The water would have rushed in and knocked them out immediately.”

This would have been the talk of the town for several days now, but I was once again astonished at Patrick’s familiarity with this very boat that tragically became a submerged coffin.

Patrick needed to attend to a project of some sort and I had finished my glass of wine, so we said our goodbyes.

Not that I ever really resonated with the trendy use of the phrase “in your wheelhouse”, but I will forever associate it now with the image of two poor fishermen going to their watery grave.

These are the highest cliffs in all of Ireland. Although one of Ireland’s best kept secrets, they rise almost three times higher than the Cliffs of Moher — nearly 2000 feet. I had never heard of them. Astonishing.

These are the highest cliffs in all of Ireland. Although one of Ireland’s best kept secrets, they rise almost three times higher than the Cliffs of Moher — nearly 2000 feet. I had never heard of them. Astonishing. Our first destination was County Cavan so that Kevin could play in the Ulster Seniors Golf Championship. The 2020 venue was Slieve Russell Hotel Golf & Country Club on their fine parkland course. We had a sumptuous room with a view of the rose garden and 18th green. To make everything more delightful, we had warm sunshine. Perfect weather and great camaraderie, unfortunately did not add up to a winning score for Kevin. In spite of those 3-putts on the tricky greens, we both thoroughly enjoyed the luxurious experience.

Our first destination was County Cavan so that Kevin could play in the Ulster Seniors Golf Championship. The 2020 venue was Slieve Russell Hotel Golf & Country Club on their fine parkland course. We had a sumptuous room with a view of the rose garden and 18th green. To make everything more delightful, we had warm sunshine. Perfect weather and great camaraderie, unfortunately did not add up to a winning score for Kevin. In spite of those 3-putts on the tricky greens, we both thoroughly enjoyed the luxurious experience. But it was the amazing prehistoric monument hiding in the Secret Garden that absolutely blew me away. It is called the Aughrim Wedge Tomb. It was originally located on the slopes of the Slieve Rushen mountain. The Quinn Group, who built the hotel, were quarrying there when it was unearthed. They engaged Mr. John Channing, Archeologist, to oversee the excavation in 1992. It was then carefully reconstructed on the grounds of the hotel rather than have it disappear forever. To some, it may be sacrilegious to move what the local folklore call “The Giant’s Grave”, but the trade off is, many more people will see it and have a peek at the ancient past of this part of Ireland.

But it was the amazing prehistoric monument hiding in the Secret Garden that absolutely blew me away. It is called the Aughrim Wedge Tomb. It was originally located on the slopes of the Slieve Rushen mountain. The Quinn Group, who built the hotel, were quarrying there when it was unearthed. They engaged Mr. John Channing, Archeologist, to oversee the excavation in 1992. It was then carefully reconstructed on the grounds of the hotel rather than have it disappear forever. To some, it may be sacrilegious to move what the local folklore call “The Giant’s Grave”, but the trade off is, many more people will see it and have a peek at the ancient past of this part of Ireland. The entire hotel property is situated about 85 miles northwest of Dublin. Many would regard it as the middle of nowhere. Our antiquated GPS took us on a network of single track roads. The grass growing down the middle, shall we say, tickled the bottom of our low-slung BMW sedan. By the time we reached the Slieve Russell Hotel, for us, it did feel like it was light years away from anything resembling a city. In other words, purely idyllic.

The entire hotel property is situated about 85 miles northwest of Dublin. Many would regard it as the middle of nowhere. Our antiquated GPS took us on a network of single track roads. The grass growing down the middle, shall we say, tickled the bottom of our low-slung BMW sedan. By the time we reached the Slieve Russell Hotel, for us, it did feel like it was light years away from anything resembling a city. In other words, purely idyllic. Knowing that Kevin and I are the leaders of this group, the hotel management put us in a magnificent suite. We were barely in the door of our luxurious light-filled cocoon, when we spotted the chocolate covered strawberries. After quickly stashing our suitcases, we smuggled the strawberries over to The Gallery Bar, where we sat outside in the glorious sunshine and enjoyed them with a lovely glass of perfectly chilled Prosecco. Well, I did. I think Kevin had a shandy.

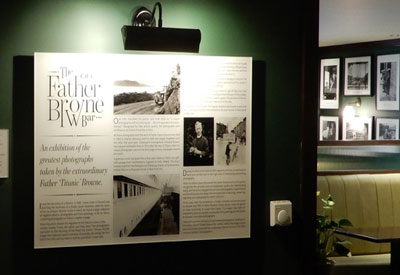

Knowing that Kevin and I are the leaders of this group, the hotel management put us in a magnificent suite. We were barely in the door of our luxurious light-filled cocoon, when we spotted the chocolate covered strawberries. After quickly stashing our suitcases, we smuggled the strawberries over to The Gallery Bar, where we sat outside in the glorious sunshine and enjoyed them with a lovely glass of perfectly chilled Prosecco. Well, I did. I think Kevin had a shandy. I may know fine art, fine framing and expert placement of a large photographic collection, but I was completely humbled by not having a clue to who is this artist. Although Father Francis Browne, a Jesuit priest, had died in relative obscurity in 1960, when his work was discovered, one critic compared him to the famous French photographer, Henri Cartier-Bresson.

I may know fine art, fine framing and expert placement of a large photographic collection, but I was completely humbled by not having a clue to who is this artist. Although Father Francis Browne, a Jesuit priest, had died in relative obscurity in 1960, when his work was discovered, one critic compared him to the famous French photographer, Henri Cartier-Bresson. I was thrilled to be able to show Father Browne’s Bar to Kevin before our dinner. While doing our site visit the next morning with Stephen Bell, the Sales Manager of the hotel, he also showed us an elegant room tucked away off the main part of the bar where we can have a private Welcome Dinner for our guests in July 2021. Then we also have the perfect venue for our musicians to entertain everybody back out in the bar area, while the pints are flowing.

I was thrilled to be able to show Father Browne’s Bar to Kevin before our dinner. While doing our site visit the next morning with Stephen Bell, the Sales Manager of the hotel, he also showed us an elegant room tucked away off the main part of the bar where we can have a private Welcome Dinner for our guests in July 2021. Then we also have the perfect venue for our musicians to entertain everybody back out in the bar area, while the pints are flowing. We packed a lot into our five-day trip to Cavan and Donegal — two counties in Ulster. (Ulster is one of four provinces of Ireland. The remaining three are Leinster to the east, Munster to the south and Connacht to the west.) We live in Liscannor near Lahinch, in County Clare. This is Munster. So it was great to see another part of Ireland. It was almost like going to another country.

We packed a lot into our five-day trip to Cavan and Donegal — two counties in Ulster. (Ulster is one of four provinces of Ireland. The remaining three are Leinster to the east, Munster to the south and Connacht to the west.) We live in Liscannor near Lahinch, in County Clare. This is Munster. So it was great to see another part of Ireland. It was almost like going to another country. When she did arrive in the dark of the night she brought the entire percussion section of a hundred orchestras with her. Drums of heroic dimensions. Timpani yes, but modest bodhrán, no. Ellen seemed to be trying to find a way to the center of the Earth. She pummeled the whole house, as if we alone stood in her way to the deep underground cave she was seeking.

When she did arrive in the dark of the night she brought the entire percussion section of a hundred orchestras with her. Drums of heroic dimensions. Timpani yes, but modest bodhrán, no. Ellen seemed to be trying to find a way to the center of the Earth. She pummeled the whole house, as if we alone stood in her way to the deep underground cave she was seeking.